Written by Nadja Sayej

The VICE Channels / Motherboard

October 28, 2013 // 11:40 AM EST

Martin Riches is an English artist with a penchant for sound. Driven by the fascination of how artificial life differs from the real thing, many of the objects which Riches has made are pre-digital masterpieces. From an aerial kite camera which overlooked the Berlin Wall—Riches has been in the city since the late 60s—to machines chatting on the radio and singing Latin hymns in church, his work personifies the intersection of where analogue meets digital. One of his more recent projects, StringThing, features two acoustic string instruments plucked with digitally-controlled fingers.

Riches started work on his most recent project, a human-mimicking singing device called the Singing Machine, in 2010. Having recently been completed, the Singing Machine is now ready to perform. The machine sings the words of Japanese poet Sadakazu Fujii, which have been set to music by Masahiro Miwa. Along with string and percussive accompaniment, the machine is already slated to perform in Japan early next year.

Rather than just showing off technical brilliance, his goal remains to show how things work. Some of his pieces use transparent materials or are left completely open so you can see the inner workings (rather than being locked up and invisible inside a closed cabinet).

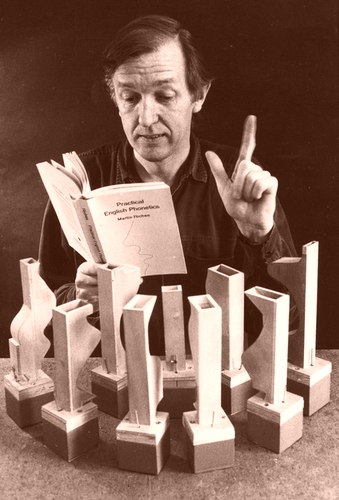

Riches teaching the Talking Machine to speak (1989) |

|

With that in mind, I spoke to Riches about his times battling Yugoslavian fighter planes with a kite camera, mastering the art of analogue speech synthesis, and machines without a soul.

Riches: I came to West Berlin in 1969 at the invitation of a German visitor who had stayed at my flat in London and said she would like to show me “the Berlin bars and the Berlin beer.” I went for the weekend, but during this weekend I was offered a design job and, since I was at a loose end, I decided to stay. I’m still here over 40 years later. Berlin has been kind to me and although it has changed a lot since the wall came down, it is still a good place to get down and do some creative work and also a good place to show it when it is done. |

The kite camera built in 1974 came in pretty handy when overlooking East Berlin from the other side of the wall. How much string did you have and how high were you allowed to go?

Actually, the kite wasn’t pointed at East Berlin. I think that would have been too difficult because the part of the wall that divided West Berlin from East Berlin ran through a built-up area full of traffic and five storey buildings. This was taken in the opposite direction. Since West Berlin was an “island” 150 km behind the Iron Curtain, it was looking out over the perimeter wall into the East German countryside.

The height limit was 100 meters of string, but I was helped by standing on a low hill of WWII rubble that had been landscaped into a park. There was another regulation that aerial photographs had to be cleared and registered with the authorities, but I never got around to doing that and I only re-discovered the photo during a recent clear out.

Do you have any more photos taken by the kite?Several, including this one of Vrboska on the island of Hvar on the Adriatic coast of 1970s Yugoslavia. Looking at Google Maps, I see that the place hasn’t changed all that much—also that my picture is much sharper than Google’s, although I have to admit that my camera was a bit lower down than theirs.

While I was taking this photo there was a fighter plane cruising around the islands, quite high up, but after a time the pilot must have spotted my kite. Nobody believes this story, but he went into a dive and flew right under the kite string—a macho pilot having fun. It was shatteringly loud! I rolled up my kite and left the scene of the crime as quickly as possible.

What do you think of the digital kite camera today?This activity is now called KAP: Kite Aerial Photography. The digital camera is on a special rig that hangs from the string and it keeps the camera both level and stable. The camera is triggered by radio control. It can also be rotated with a servo to do panoramic shots. It's a sophisticated system that gives brilliant results. Some of the kites are parafoils which means they can be folded up very small.

I was doing this stuff in the 1970s with a wood-framed box kite, a cheapo camera, and a burning fuse to release the shutter. I hadn’t heard of other people making kite photos at that time, but I am certainly not claiming “I did it first.” There is a famous kite photo made by George Laurence, San Francisco in Ruins, taken after the 1906 earthquake with a panoramic 17 x 48 inch (!) plate camera, and the very first kite photos were made in 1887.

|

|

The speaking machine and singing machine are timeless inventions which never cease to garner interest. What fascinates you about electronic sounds and how it differs from the human voice?

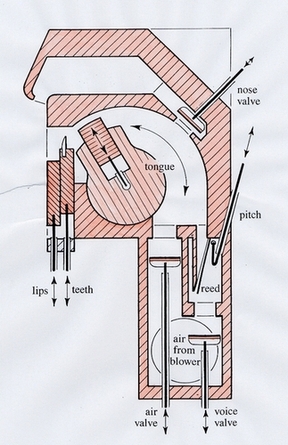

Speech synthesis is the art of producing what sounds like human speech without using any form of recording. My Talking Machine, MotorMouth, and Singing Machine talk like you and me. That is, with vocal chords (of a sort!) and a flow of air. They are not electronic voices and there are no loudspeakers involved. You can see how the speech sounds are produced. In the case of the Singing Machine and MotorMouth the mouth is built using Plexiglas so you can see the lips and tongue moving and valves opening to admit the air. |

The speech sounds are produced acoustically (as in a musical instrument) so I suppose you could call this “analogue speech synthesis,” although the motors for the tongue and lips are digitally controlled. Electronic synthetic speech, on the other hand, comes out of a loudspeaker. It is becoming so good that it is difficult to distinguish it from a recording. But I am more interested in making something where you can actually see how it works.

What are the StringThing instruments which were recently shown in Poznań? They look like a hybrid of analogue and digital.“Hybrid of analogue and digital” is a perfect description and it applies to a lot of the stuff I do. These are two string instruments with real strings that are bowed and plucked and produce their sounds in an analogue manner like musical instruments. But the things that are bowing and plucking them and the “fingers” that stop the strings are digitally controlled, either by a computer or by a built-in chip.

What prompted you to create MotorMouth back in the 1990s? Can anything be automated, by your standards? You've quoted Heinrich Heine, who said "you can mechanize anything but the soul."MotorMouth goes a step further than the earlier Talking Machine that had 32 pipes. MotorMouth has just one pipe: a model of the human vocal tract with lungs (a blower), a mechanical tongue that moves to and fro, up and down, and lips and teeth that open and close.

Heinrich Heine wrote a satirical story about an English mechanic who built an android that had everything—everything except for a soul. "In other words, a perfect English gentleman," as Heine expressed it. The android was well aware of this deficiency and hounded its inventor across Europe screaming, "Give me a soul!" As an English mechanic, I quite enjoy this story.

Can anything be automated? I suppose so, sooner or later, but not by me. We will soon have cars that drive by themselves, but they'll perhaps be less fun. My interest is in making things so one can see how they work; the opposite of a "black box".

The Singing Machine is in its third version and, having made a lot of very small adjustments, it is now just about finished. It has been programmed to sing a poem by Sadakazu Fujii: hitonokiesari – people vanish, set to music by the composer Masahiro Miwa and accompanied by nine instrumental players.

It will be featured in a concert Hybride Musik at the Philharmonie in Essen, Germany, on October 26, and at the Aichi Arts Center in Nagoya on February 9 and at the Asahi Hall in Tokyo on February 11. The Singing Machine sings a Latin hymn as a demo on my website. I enjoy the solemnity and elegance of Latin hymns; they are slow and within the range of the machine’s baritone voice.

My next project will be four similar monk-like voices and I am hoping that Masahiro Miwa will compose a work for them that is suitable for a space with a very long echo, like a church. This would be the third project we have worked on together; the first one was our Thinking Machine.

Your work ranges far and wide, from machines to kites, hang gliders and drawings. Do you define yourself as a multi-disciplinary artist, or is it more about each idea taking its own form?I just follow my interests as they come along. At the moment I’m fascinated by the machine built in 1912 by the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Quevedo that could play an unbeatable chess endgame: white king and rook against the black king that is played by a human being. It is very well documented and I just wrote a program which reproduces the algorithm he used so that I could try and understand how this beautiful and intelligent mechanism works. (He built two versions and they are both running and on display in Madrid.)

Also on the level of sublime technical and mechanical ability, I am utterly seduced by the work of Tatiana van Vark. I admire them but it would be foolish to copy them, even if I could. I contemplate these beautiful projects and then hope that the Muse will give me a hint to do something of my own.