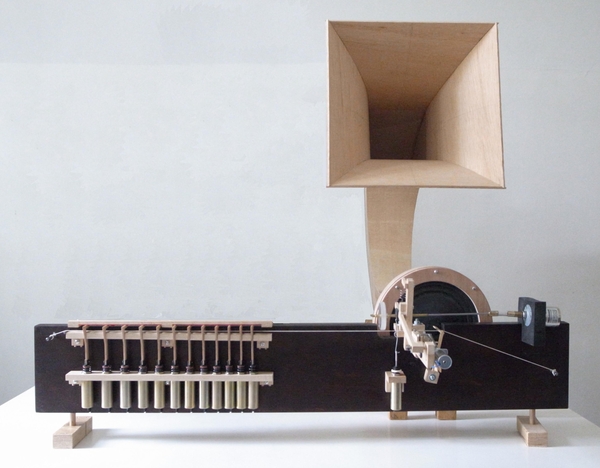

One of the two instruments, of similar construction but mirror images of each other

One of the two instruments, of similar construction but mirror images of each other

A test tune for the prototype on just 4 notes by Makiko Nishikaze: click here

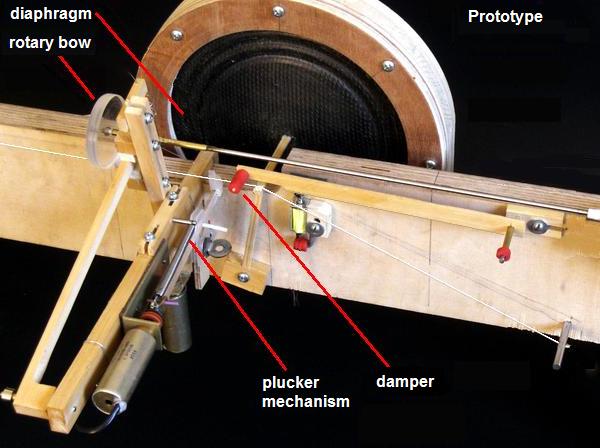

(At this point only 3 fingers were fitted.)

The damper worked fine on the prototype but did not seem to be all that useful so I left it out.

I also experimented with a vibrato using a motor to operate a wammy bar and with an automatic tuner but did not

pursue these features further ... anything to keep it simple.

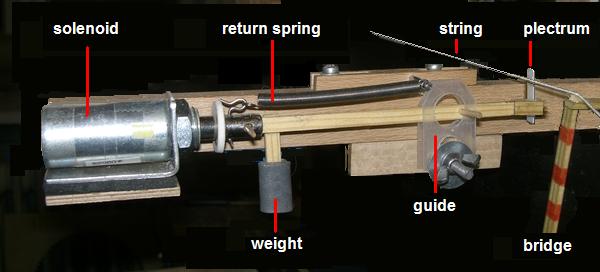

Plucker mechanism

The plectrum plucks the string when it is pulled by the solenoid but then, on its return,

it ducks under the string to avoid playing it a second time.

The inertia of a weight forces the plectrum upwards to play and then downwards on its return.

The design was inspired by the picker of the Encore Banjo. This rare automatic instrument was

kindly demonstrated for me behind the scenes at the Ukai Museum, Kawaguchiko, by its restorer, Norio Isogai.

|

|

Bow mechanism A disk of Plexiglas (8 mm thick, 48 mm diam.) turning at about 100 rpm. Its surface is slightly cambered, finished with coarse sand-paper and lightly covered with hard violin rosin. The bow hovers about 1 mm above the string and is pulled downwards by the solenoid to play it. The position of the lower white felt stop determines the bow pressure and the volume. An application of rosin lasts for at least 10 minutes. I may add a device to apply rosin automatically. |

|

Diaphragms The carbon fibre diaphragms were formed in a sandwich with the following 5 layers:

|

|

Horns The horns were made of two kinds of plywood: flat and bendy. The bendy plywood parts had rebates cut into their edges so it could all be fitted together without using a core. Here the bendy skin is being glued down with the help of some bungee rubber clamps. The tape is to catch the glue squeezed out of the joints. This horn has a pyramidical bell but I replaced it with a curved one. |

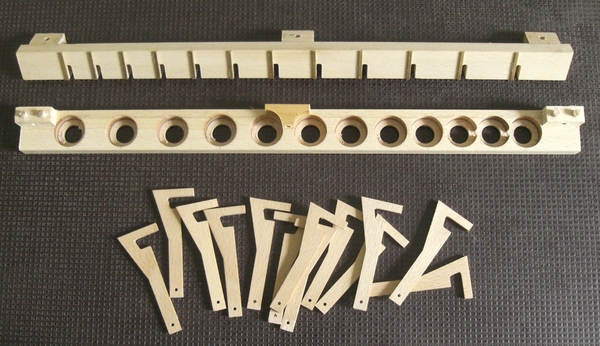

Fingerboard, holder for solenoids and fingers

These parts were cut out with the help of my home-grown CNC milling machine.

Finding the correct angle of the fingerboard relative to the string was more difficult:

Too shallow and the string touched the next fret and made a buzz.

Too deep and the solenoids for the higher notes had trouble depressing the string.

The concert was organised by the Münchner Gesellschaft für Neue Musik

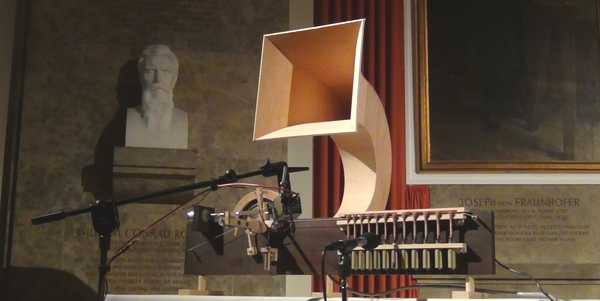

StringThing under the stony gaze of the giants of German science in the Hall of Honour

of the Deutsches Museum in Munich; apparently the largest science museum in Europe.

Video cameras were focused on the mechanisms of the machines which were projected onto a large screen

during the performance. They played things for things by Makiko Nishikaze and Saitenmusik

(String Music) by Roland Pfrengle. Roland also designed an interface for this machine.

String Thing at Galeria Naprzeciw, Poznań, organised and curated by Mikolaj Polinski

The two instruments can also be set up to run in stand-alone mode without a computer: each half of the duet is programmed onto its own Atmega8 chip and these two chips are then plugged into their respective machines. The two machines can then be placed any distance apart but as long as they are both switched on at exactly the same moment they will then run independently of each other but still play in time together.

Makiko Nishikaze’s things for things is programmed to run in this way:

The first page of the 10-minute duet things for things.

The first page of the 10-minute duet things for things.

It was also played in 2016 at Daniel Löwenbrück's

Rumpsti Pumpsti gallery

in Berlin.

to music machines

to music machines