In 1990 I was invited by Friedrich Schenker to take part in a concert in the series

MUZIKA contemporary composers interpret music-related works of the insane.

The scores and notations were taken from the Prinzhorn Collection which is devoted to the artistry of the mentally ill

The concert was presented in Berlin at the Academy of Arts ( East Berlin) and my Four-Piece Percussion Installation accompanied members of the Chamber Ensemble for New Music Berlin (KNM) in 13 March-Waltzes from Scores by Oscar Herzberg.

Studying the programme notes of the concerts I noticed a small reproduction of another score, one of the Three Leaves (Drei Blätter) by Lorenz Mathias Seitz, together with a text:

Lorenz Mathias Seitz, a labourer, was born in 1877 in Oeschelbronn. While still in good health he served 5 years in the Foreign Legion and also travelled alone through North Africa and the Near East. During this period he learnt Arabic and converted to Islam. In 1921, suffering from schizophrenia, he was committed to the Wiesloch asylum. His Three Leaves, written on toilet paper, show continuous lines of script whose characters consist of right angles in various positions combined with up to three additional dots. We know neither the meaning of this text nor of its characters. They might well be some kind of secret code or an attempt at a stylised Arabic script.For a longer account of his tragic but adventurous life, see here.

The notations by Lorenz Mathias Seitz were interpreted by Sven-Åke Johansson as an "alphabet of gestures with individual percussive sounds" in his Solostück für Konzertbecken - a solo for symphonic cymbals.

Looking at the score it occurred to me that Seitz's composition might be open to another interpretation. I was reminded of what - in England at least - is called the code that every schoolboy knows;, also "the Masonic Code" or, more prosaically, "Pig Pen".

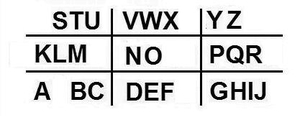

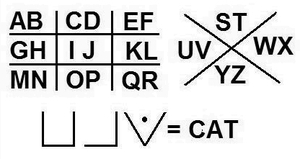

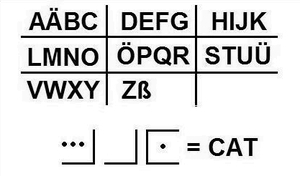

Coding and decoding are performed with the help of a grid and a diagonal cross. The 26 letters of the English alphabet are inscribed, two in each space:

In the encoded message each letter is represented by the outline of its enclosing space whereby the second letter in the space is identified by an additional dot. The example shows the symbols for the word CAT.

Seitz's notation seemed to be a variation of this system. With his three dots he could accommodate up to four letters into each box and, if his message was in German, he could include the S-Z ligature ß and the umlauts Ä, Ö and Ü and still have room for more:

I made many attempts to interpret the small picture in the programme notes according to variations of this grid but without success. I then wrote to the organiser of the concert, Frau Dr. Inge Jádi, the curator of the Prinzhorn Collection, asking her for reproductions of the Three Leaves. Having received three large photographs and an encouraging letter I set about solving the problem by using a letter-frequency table rather than by trying to reconstruct the grid.

First I had to make a guess at the language. Seitz was a native German speaker who also spoke Arabic and, with his five years in the Foreign Legion, he must have spoken French.

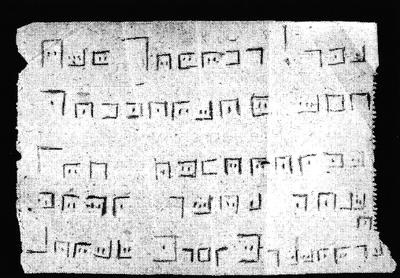

The text was not written as a continuous string or in regular groups but - insecurely - was split up into individual words: many long words interspersed with frequent three- and four-letter words which is a characteristic of German. With this in mind I noticed that many of the symbols were written large, but not like the initial capital letters of German nouns; these large symbols were at the ends of the words. Evidently the message was in mirror writing - written from right to left - perhaps inspired by Arabic? The symbols could also be read the right way round from behind, by holding the spartanic toilet paper of the time up against the light.

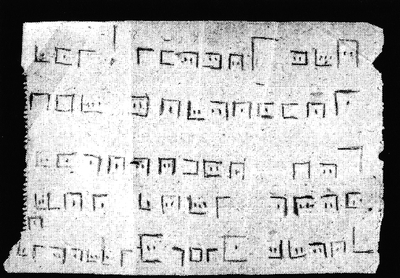

Inv. Nr. 4400 / 1 recto

Inv. Nr. 4400 / 1 recto

|

|

Nr. 4400 / 1 verso

Nr. 4400 / 1 verso

|

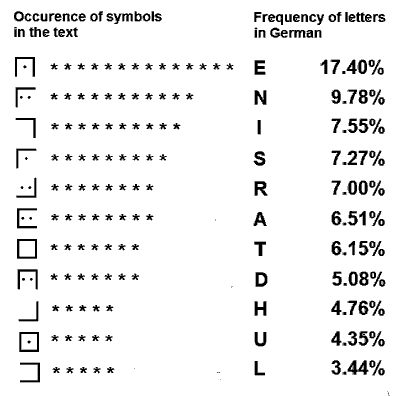

Thanks to Dr. Jádi I now had a larger sample to work on so I made a table comparing the frequency of the symbols in the text with the frequency of letters in the German language.

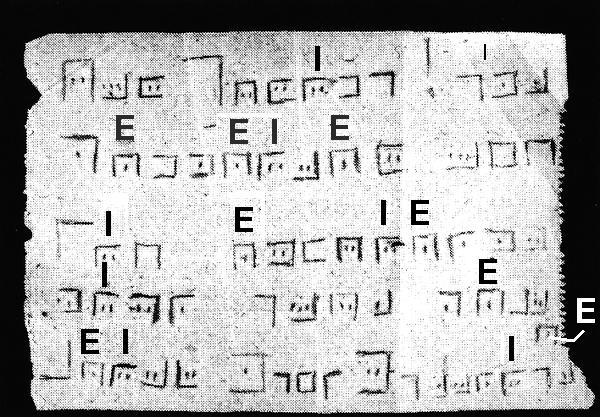

According to the table, the most frequent symbol was probably an E and I soon found that my suspected E and I symbols made a convincing German pattern.

Inv. Nr. 4400 / 1 recto.

Inv. Nr. 4400 / 1 recto.

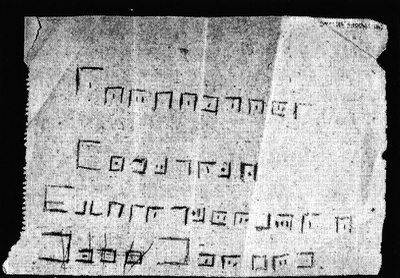

To cut a long story short, the breakthrough came when I decided that the last word could be "Matthias". After that everything fell into place and I concluded that Seitz was using an inverted grid quite like the diagram below. The empty spaces could have been used to accomodate the umlauts.